Sonics of Home: Music From the Welsh Mines, Paul Robeson and Taos Amrouche

Dear friends,

I pray this finds you well and in good spirits. I’ve just returned from one of a number of recent trips to Wales to visit my great-aunt; a ray of sunshine that’s come into my life in the last year after extensive family history research I wrote about here. She’s our last living Welsh relative, and her reappearance has opened up a whole new constellation for me and my family. She and my grandfather had lost touch for 70 years.

Driving through the green valleys to visit the resting places of our Irish ancestors on my last trip, I felt some kind of pull. Some kind of aliveness, some familiarity. As well as some kind of unfamiliar too. Of here, but not of here.

We dropped down through the Vale of Clwyd, through the land of Iron Age Forts and mountains - often understood as ancestral figures in Welsh tradition - and past Moel Famau (Mother Hill) and my aunt told me we’d entered the Lands of the Ancient Gods now.

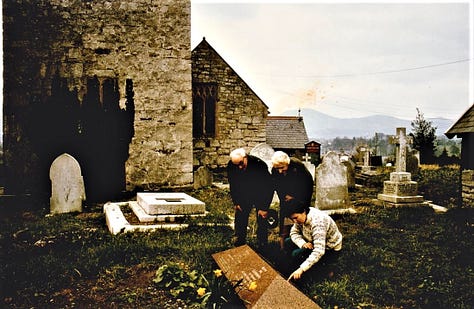

I could see the cobbled stones, the steep steps and the ivy-covered gateway coming into view. This church and these roots I’d been following my way back to for so long. I recognised it from the photos we had of my great-grandparents visiting - it was from these that I located the church, and in that way that threads always interconnect, finding this one eventually led me to my great-aunt.

Our ancestors’ vault was carved from a rich red granite stone, unlike any others in the graveyard. I later discovered Ruthin means “red”, after the local sandstone. But this granite came from Scotland. Why did these railway porters and labourers pay what must have been a substantial sum to bring it here to their final resting place? Did they migrate from Scotland, to Ireland, on to Anglesey and then to this Welsh village?

We laid dried roses and I read a piece I wrote in a moment of longing for a people, place and language I’d never known - A Bridge that Crosses the Oceans - Chi qntera li qtaa almohit. Inside the church, we sat on a pew watching the light catch the floor tiles, and I pulled up one of my playlists I return to when I feel those pangs of longing.

And the first track I saw was Ave Verum from the Music From the Welsh Mines album by the Rhos Male Voice Choir, a song I added long before learning of my family’s connections there. We listened to these mournful and haunted voices from the past, recorded in the shadow of a mining accident the choir experienced the day before, and carrying the grief of the recent Gresford disaster which killed 266 people.

Scrolling down, I saw Joe Hill by Paul Robeson - and I pulled up my favourite recording of him singing it to Welsh miners in 1949. Robeson’s connection with Wales began when he met striking miners in London and deepened through a shared appreciation of each other’s singing traditions.

Despite differences, they found some kinship in their struggles; Robeson as an African-American working-class activist and the miners as working-class communities rising up against poverty and exploitation.

That night, we stayed up talking into the early hours, and before we shuffled off to bed we listened to another track on the playlist by Taos Amrouche - a Kabyle singer from Algeria. Her voice conjured up any remaining dormant spirits in the family photos that lay on the floor in front of us.

We said goodnight, knowing it’s never goodnight.

In other news, I’m honoured to say that my film Bladi - My Country has been selected for the MENA Film Festival in Canada, and will be screening there in 2026.